Exact probability

–

Decimal form

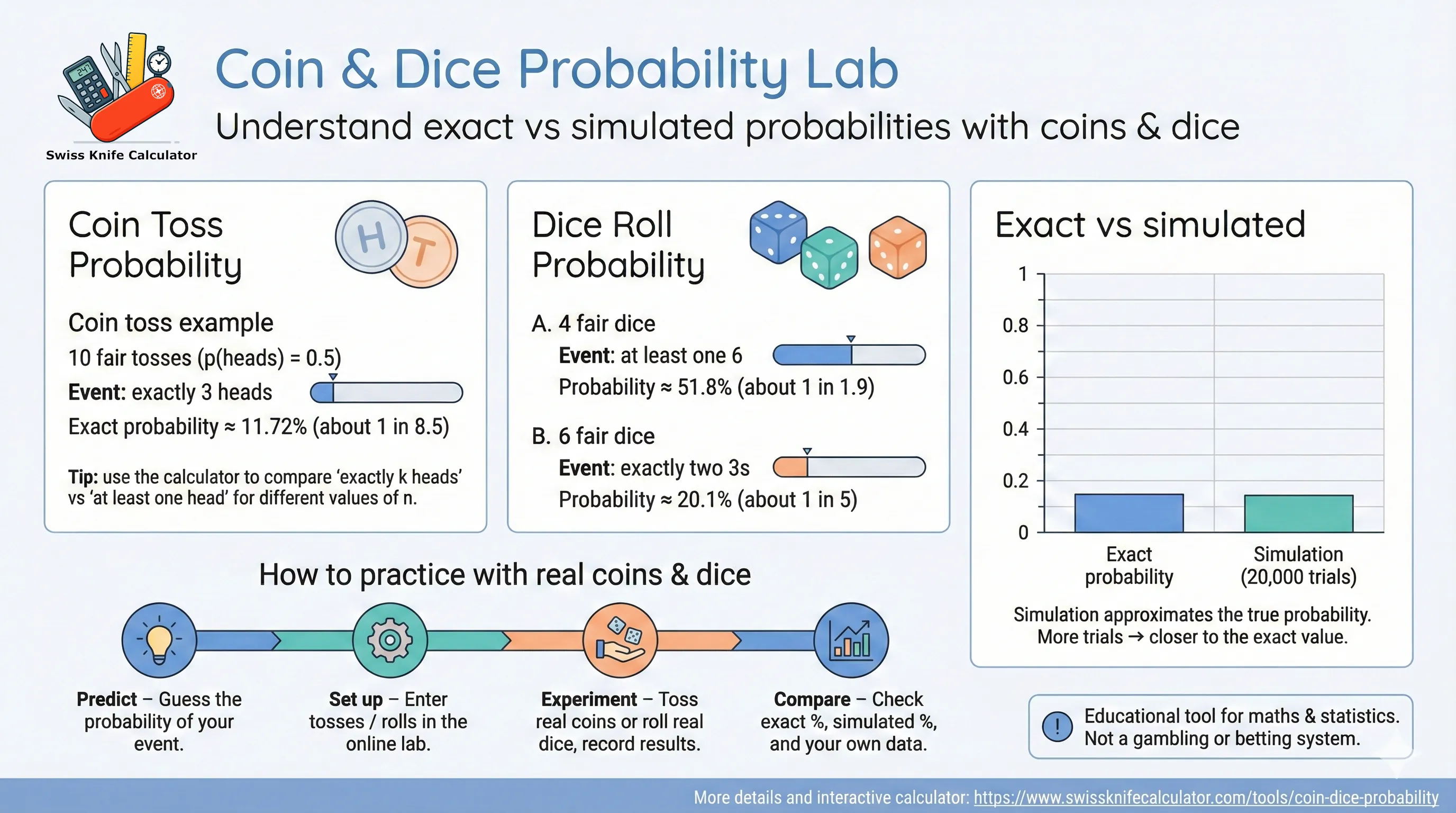

Calculate exact probabilities for coin tosses and dice rolls, then verify them with Monte Carlo simulation, histograms, and clear “1 in N” odds.

Use this coin toss probability calculator and dice roll probability simulator to configure experiments, choose your event (exactly k heads, at least one 6, sum ≥ S, custom multinomial categories) and compare exact probabilities with simulated frequencies.

p(Tails) = 0.50

Recommended range: 1–200 for clear charts.

On smaller screens, results will appear below. The page will automatically scroll to the results after each calculation.

Configure an experiment and press Calculate to see the exact probability, 1-in-N odds, and a comparison with Monte Carlo simulations.

–

Decimal form

–

Probability as %

–

Human-friendly odds

–

Rational approximation

–

E[X] for this experiment

–

Standard deviation (σ)

When you calculate, this panel will show which distribution was used (binomial, multinomial, or dice-sum model), the exact parameters (n, p, k, sums, etc.), and the steps leading to the final result.

Simulation status: No simulation run yet.

Simulated probability: – vs exact value

Difference (sim − exact): –

A few randomly chosen trials from the simulation. For coin experiments you’ll see H/T sequences; for dice experiments, rolled faces and sums.

Run a calculation to see a quick snapshot of recent trials and how often the event occurred.

YES = event occurred · NO = event did not occur

This interactive Coin & Dice Probability Lab combines a coin toss probability calculator with a dice roll probability simulator in one browser-based tool. It is ideal for students, teachers, data-science beginners and board-game designers who want to understand how random experiments behave in practice.

The coin module lets you:

n.p(heads) = 0.5) and a

biased coin with any probability of heads between 0 and 1.The dice module allows you to:

For each setup the lab computes:

Together with other probability tools on SwissKnifeCalculator — such as the Ball & Urn Probability Calculator, the Deck of Cards Probability Calculator and the Advanced Random Number Generator — this lab forms a complete probability & statistics toolkit for school, university or self-study.

📚 Educational note: This coin and dice probability calculator is created for learning, teaching and intuition-building. It is not a gambling system and does not increase your chances of winning in any real-life game.

Under the hood the Coin & Dice Probability Lab is powered by binomial and multinomial probability models, combined with Monte Carlo simulation to show how theory behaves in practice.

| Scenario type | Mathematical model | Typical question |

|---|---|---|

| Coin tosses (heads vs tails) | Binomial distribution | “What is P(exactly 3 heads in 10 tosses)?” |

| Target face on dice (6 vs not-6) | Binomial distribution | “What is P(at least one 6 in 4 rolls)?” |

| Counts of all die faces (1–6) | Multinomial distribution | “How many 1s, 2s, … 6s do we expect in 60 rolls?” |

| Sum of several dice | Exact enumeration or simulation | “What is P(sum ≥ 10 with 3 dice)?” |

A sequence of coin tosses is a classic Bernoulli process. Let:

n = number of tossesp = probability of “success” (for example heads)X = number of successes (heads) in n tosses

For a fair coin p = 0.5. For a biased coin you choose any p between 0 and 1.

The probability of exactly k heads is given by the binomial formula:

P(X = k) = C(n, k) · p^k · (1 − p)^(n − k)

The calculator uses this expression whenever you request “exactly k heads” in the coin module.

“At least / at most” questions are handled by summing or complementing binomial probabilities, for example:

P(X ≤ 2) = P(X = 0) + P(X = 1) + P(X = 2)P(X ≥ 1) = 1 − P(X = 0)Many dice problems are also “success vs failure” experiments. For a fair six-sided die:

p = 1/6 for “rolled the target face” (for example a 6)1 − p = 5/6 for “anything else”

If you roll a die n times and define success as “rolled a 6”,

the probability of exactly k sixes is again:

P(X = k) = C(n, k) · (1/6)^k · (5/6)^(n − k)

This is how the tool answers questions like “exactly two 3s in 6 rolls” or “at least one 6 in 4 rolls”.

For a custom or loaded die, each face can have its own probability

p1, …, p6 with p1 + … + p6 = 1.

After n rolls the joint probability of seeing counts

(x1, …, x6) is:

P(X1 = x1, …, X6 = x6) = n! / (x1! x2! … x6!) · p1^x1 · … · p6^x6

The lab uses this structure to compute expected frequencies and to generate theoretical histograms of face counts that can be compared with your simulated rolls.

For small numbers of dice (for example 2 or 3) the tool can enumerate all

outcomes exactly. With three dice there are 6^3 = 216 possible triples.

For larger numbers of dice, a high-quality Monte Carlo simulation

is used so calculations remain fast in your browser.

The simulation module runs thousands of virtual experiments using JavaScript’s pseudo-random number generator. Each trial reproduces your full configuration (number of tosses, coin bias, number of dice, target event, etc.) and records whether the event occurred.

The fraction of successful trials gives the simulated probability. As you increase the number of trials, this value will typically move closer to the theoretical value — a practical illustration of the Law of Large Numbers.

🔐 These random numbers are suitable for education and general simulations, but they are not cryptographically secure and should not be used for security-sensitive applications.

The following examples are chosen so that they can be reproduced directly inside the Coin & Dice Probability Lab. Percentages and “1 in N” odds are rounded but match the calculator results very closely.

Toss a fair coin 10 times. What is the probability of exactly 3 heads?

n = 10 tossesp = 0.5 (fair coin)k = 3 successes (heads)P(X = 3) = C(10, 3) · 0.5^10 ≈ 0.1172

That is about 11.72 %, or roughly

“1 in 8.5” ten-toss experiments.

In the lab select the coin mode, set n = 10,

choose “exactly k heads” and set k = 3.

Toss a fair coin 5 times. What is the chance of getting at least one head?

Compute the complement “no heads” and subtract from 1:

P(no heads) = 0.5^5 = 1/32 P(at least 1 head) = 1 − 1/32 = 31/32 ≈ 0.9688

So the probability is about 96.88 % —

this event is “almost certain”.

In the calculator choose “at least one head” and n = 5.

A coin is biased so that p(heads) = 0.6.

You toss it 8 times. What is the probability of getting

exactly 5 heads?

n = 8, k = 5, p = 0.6P(X = 5) = C(8, 5) · 0.6^5 · 0.4^3 ≈ 0.2787

This is about 27.9 %, or roughly

“1 in 3.6” eight-toss experiments.

In the lab, set n = 8, k = 5 and

move the coin-bias slider to 0.6.

Roll a fair 6-sided die 4 times. What is the probability of getting at least one 6?

P(no 6 in one roll) = 5/6 P(no 6 in 4 rolls) = (5/6)^4 ≈ 0.4823 P(at least one 6) = 1 − (5/6)^4 ≈ 0.5177

So the probability is about 51.8 %, or “about 1 in 1.9” four-roll experiments. In the dice module choose 4 rolls and event “at least one target face = 6”.

Roll a fair die 6 times. What is the chance of seeing exactly two 3s?

p = 1/6n = 6, k = 2P(X = 2) = C(6, 2) · (1/6)^2 · (5/6)^4 ≈ 0.2009

That is roughly 20.1 % or “about 1 in 5.0” sequences of 6 rolls.

Suppose a die is loaded so that p(6) = 0.3 and all other faces together

share the remaining probability 0.7.

If you roll it 5 times, what is the probability of getting

at least one 6?

P(no 6 in one roll) = 0.7 P(no 6 in 5 rolls) = 0.7^5 ≈ 0.1681 P(at least one 6) = 1 − 0.7^5 ≈ 0.8319

So the event occurs with probability about 83.2 %, or “1 in 1.2” five-roll experiments. In the lab choose a custom die, set the probability of 6 to 0.3, and select “at least one target face”.

Roll 3 fair dice and add the pips. What is the probability that the sum is at least 10?

There are 6^3 = 216 equally likely outcomes.

Exactly 135 of those have a sum of 10 or more, so:

P(sum ≥ 10) = 135 / 216 ≈ 0.625

The probability is 62.5 %, or “about 1 in 1.6” three-dice rolls. In the dice module pick 3 dice and event “sum ≥ 10” to see the same result plus a histogram of simulated sums.

✅ Try entering these examples into the Coin & Dice Probability Lab and inspect: the exact probability, the percent value, the “1 in N” odds, and the simulation chart.

Probability becomes much easier when you can see how abstract formulas behave. The results panel and charts in this lab turn each configuration into a visual story:

As you increase the simulation size you can watch the bars and histogram converge toward the theoretical curve, demonstrating fundamental ideas like the Law of Large Numbers and the Central Limit Theorem in a highly visual way.

This tool teaches: exact probability (theoretical math) vs simulated probability (Monte Carlo trials).

For even more visual experimentation with randomness, you can combine this tool with the Random Number Generators hub and the Ball & Urn Probability Calculator to build complete lesson plans on sampling, distributions and risk.

You do not have to stay on the screen only. This Coin & Dice Probability Lab is designed so that you can practice real experiments at home, in the classroom or in a training room, then use the calculator to evaluate your “score” and see how close you are to the theoretical probability.

After a few rounds you will see a clear improvement in how accurately you can “feel” the difference between rare, occasional and common events.

💡 Tip: The goal of these practice sessions is not to “beat randomness”, but to align your intuition with how coins and dice truly behave. The closer your mental picture matches the calculator’s results, the stronger your real-world decision-making under uncertainty will become.

For more structured probability experiments beyond coins and dice, explore the Deck of Cards Probability Calculator and the Ball & Urn Probability Calculator. All three tools share the same clean interface and help build a strong, intuitive understanding of discrete probability.

It is a browser-based coin toss probability calculator and dice roll probability simulator. You can model experiments, compute exact probabilities, run Monte Carlo simulations and visualise how often different outcomes occur.

Yes. For coins you can set any probability of heads between 0 and 1. For dice you can assign custom probabilities to each face as long as they add up to 1. This is perfect for exploring unfair games and weighted experiments.

For “number of successes” questions (like heads or sixes) it uses the binomial distribution. For full patterns of die faces it uses the multinomial distribution. For sums of dice it uses either exact enumeration (for small numbers of dice) or a high-precision Monte Carlo simulation.

The exact probability comes from mathematics: it assumes a perfect model and infinite repetitions. The simulated probability is the fraction of Monte Carlo trials where the event occurred. With many trials the simulated value will usually sit very close to the exact value, but it always shows some random variation.

For quick intuition, a few thousand trials are usually enough. If you want a very tight match between theory and experiment, increase the number of trials. The trade-off is that more trials take slightly longer but reduce random noise in the result.

Every run uses a new stream of pseudo-random numbers, so the simulated percentage will jump around a little. This is normal and is a great way to illustrate how sample results fluctuate even when the underlying probability stays constant.

The “1 in N” wording tells you how rare an event is in everyday language. For example, if the probability is 0.02 (2 %), the odds are roughly “1 in 50”. It does not mean the event will occur exactly once in every 50 attempts; it means that over many repetitions the long-run frequency is around 1 out of 50.

It is best used as a companion, not a replacement. Try to solve coin and dice problems by hand first, then use the tool to check your answers, explore “what-if” scenarios and deepen your intuition.

No. This calculator is intended only for education and exploration. It does not provide betting advice, does not predict real-world lottery or casino outcomes and should not be used as a gambling system.

Yes. Use the integrated copy / print / export buttons to copy the result summary, create a print-friendly view or save a PDF snapshot of your last experiment including configuration, exact result, simulation metrics and charts.

Yes, it is free to use in classrooms, private tutoring, online courses, study groups and self-study sessions. You are welcome to share links or project it on screen, provided you keep the educational, non-gambling context.

All three tools rely on the same core ideas: binomial, hypergeometric and multinomial distributions. Coins and dice are the simplest examples; coloured balls and playing cards extend the same concepts to more complex real-world settings.

A basic understanding of fractions and percentages is enough to get started. Explanations are written to be friendly for school students, but the tool is robust enough for university-level introductory statistics courses.

No. The simulations rely on the standard random number generator built into your web browser. It is excellent for education and general statistics, but it is not suitable for cryptography, security tokens or real-money gambling.

Important: The Coin & Dice Probability Lab is provided for educational and exploratory purposes only. It must not be used as a real-money gambling system, financial decision engine or security-critical tool. Always seek professional advice for decisions that carry legal, financial or safety risks.

Reviewed: December 2025 – formulas, examples and explanations checked for clarity and accuracy.